|

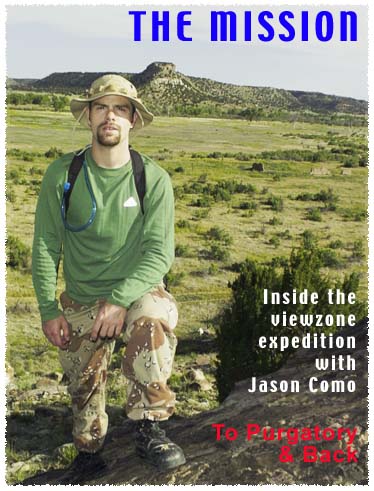

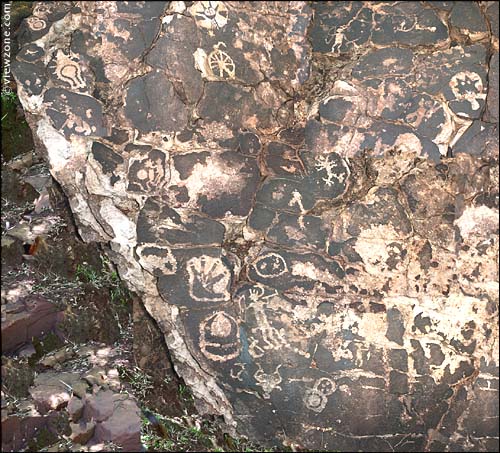

Shortly after volunteering for the job of ZoN Content Programmer, Jason Como, found himself in one of the most remote parts of the lower 48 states directing a military style reconnaissance mission. He knew ViewZone Magazine's reputation for thorough investigative reporting, but Jason never realized the extremes that some stories demand. More than once, Jason's training as a Navy Seal would save the expedition. The object of the mission seemed simple enough. Three specially chosen individuals converged on the small cattle town of La Junta, Colorado. Each was trained to use state-of-the-art electronic recording equipment and satellite navigation devices. The group had aerial photographs and infrared satellite scans to guide them to their targets: a collection of deteriorating rocks with faint traces of forbidden and suppressed history. The site of this collection of ancient writing is on private land. For a number of political and economic reasons, ranchers have good reason to fear the exposure of this discovery to the outside world. Once detected, our team would be met with force and immediately ejected. We had to get in, document the material, and get out.

|

|

Just getting to La Junta, Colorado is a long trip. It's not near anything. Roads go perfectly straight for 40 miles and the land is full of grazing cattle. The area is actually a desert, unusual for Colorado, with temperatures reaching 120 F and the landscape rich in cactus and yucca plants. The high altitude, ultraviolet rays and a steady wind can rapidly dehydrate a man. Perspiration is stripped from the skin so fast that you hardly ever experience sweat. Running through this arid, inhospitable land is a river, the Purgatory. There's a tradition with the name, dating from the days when the Spanish killed the native people for God. Now it was "Purgatory" for thousands of cattle who would realize too late that this perfect "open range" led to a slaughterhouse. On the way into town the local radio continued to mention how proud the community was of their high school's graduating class. Several businesses ran ads that mentioned graduates by name, reminding them to stop by for their complimentary "twenty pounds of meat." Our group was vegan. We knew this would be a dead giveaway that we were "outsiders." We avoided dining in local hot-spots like the Stockade, Rocky's Rib Joint or The Hog's Breath, even though we were told that they had salad bars. Mexican restaurants were plentiful and, as long as they didn't use lard, we were able to eat like the locals. We stayed in the only good motel in town. It had a free Tang and Coffeemate breakfast with real toast and instant coffee. In fact, it was such a good motel that the locals stayed there just for the luxury and a chance to swim in the indoor pool. It seems the Motel-8 was also a popular rendezvous for high school dates, truck drivers and waitresses, and an occasional traveling salesman with new and quicker ways to kill, bleed and dismember those big-legged Holsteins. During the day we drove 30 miles to our arranged coordinates and hiked ten to twelve additional miles to the rock sites. We did this loaded with our equipment and batteries. Rattlesnakes, tree-sized poison ivy, mud hornets, prickly cactus and sharp yucca leaves demanded our complete attention during these treks. We each carried large Camelbak water bags on our backs and kept track of one another by mid-band radios. Once at the sites there was hardly time to rest. We would unpack the equipment, record the known rock carvings and then sweep the area for new petroglyphs. With ropes and harnesses we managed to repel down some of the cliffs and to mount some of caps of the high rocks. Many new petroglyphs were found and recorded, despite some literal cliff-hangers that almost placed us in the real Purgatory. Near death experiences aside, everything went according to plan until the day we were busted. One of our coordinates was off. Geo-coordinates taken prior to May 2000 were not accurate. This "introduced error" was done by order of the military to prevent domestic strategic targets from being the object of a cruise missile attack. The coordinates sent from the orbiting satellites were about 60 yards off in any direction and several hundred feet in elevation. Our equipment did not have this error but could only point us to the old set of coordinates. This miscalculation took us right next to the main road of a rancher's home. Before we could extract ourselves we were met with hired hands and pick-up trucks. Our cover story didn't work. It was a good one, too. The ranchers here were simple but not dumb. We drove back to town with our first real defeat. News travels fast in a small town. By the time we had driven thirty miles back to our motel, the manager had activated a blinking red light on our phone with a message to call her. Despite being gone from just after dawn, the manager was accusing us of smoking in the motel room that afternoon -- a non-smoking room that we had requested because we don't smoke -- and was ejecting us immediately. We argued with her and demanded an apology but she refused to give in. She claimed that her nipples got itchy whenever she was around "that stuff" and insisted that this had happened to her outside our room. It was hopeless. She was wrenching at her bra just looking at us. But this excuse was all fabricated to remind us that our activity was unwelcome. When we threatened not to pay for the few days we had stayed, Arlene, the manager, frantically called the police. We left the motel parking lot just as the police arrived, hit the backroads and headed East to the retired "biker" town of Los Animas. In Los Animas we were safe. People admired conflicts with the law and considered it a kind of "checks and balances" of their personal freedom. We stayed with these kind people for the duration of the expedition and felt the bad vibes each time we had to pass through La Junta. On the return trip we learned the words to Slim Shady's first album and laughed about Arlene's itching breasts. We dreamed of eating some good veggie food and a cup of Starbucks coffee. Soon we would be out of Purgatory. Amen. |

|