|

Following the Ramlat al- Sab'atain Road

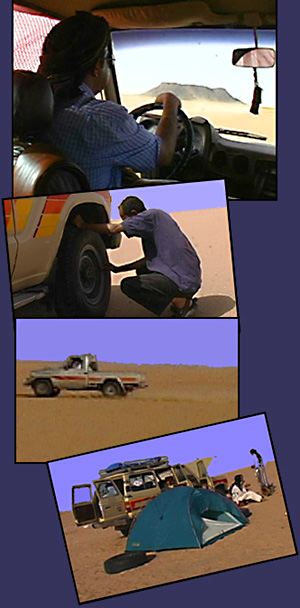

The Bedouins were there to meet us as we pulled off of the asphalt road and on to the sand of the Empty Quarter. Our Land Cruiser and the Bedouin pick-up sat together quietly in the morning light while Nasser and our escorts discussed the route. A loud hiss began outside the truck near the tires.

"Um, Nasser, what are you doing?" I asked.

"To gain grip on the sand," Nasser grinned at my confusion. "A small amount of air will be let out."

We entered the Saidah Desert on the Ramlat al- Sab'atain Road. This road, we were told, was temporary and would disappear within hours, obliterated by the desert winds and covered by the massive dunes. Giant mountains of fine sand rolled in from the East and seemed frozen in time as they crashed against the base of jagged, black volcanic mountains.

This harsh environment changed everything. Gold and Ryals were useless here. Abdul, our driver, and water were now indispensable. With qat in his cheek, Abdul turned our metal steed and headed into the sands with confidence.

The Bedouins navigated by the Sun and stars. They rushed ahead of us, raising a cloud of dust, and disappeared from view. Within moments they would reappear atop the high dunes and wait for us to catch up. The ride was hot but made pleasant by lots of bottled water, some fruit and the Hadhramaut style Yemeni music that Nasser played on the stereo.

We all briefly dozed off -- except Abdul -- hypnotized by the music and lulled by the cyclical hum of the 4-wheel drive as we bounced over the stark landscape.

|

Tam'noh

Incense and spice laden camels were treated to a rest at the Tam'noh of antiquity. Large brick lined vaults are all that remain of the major caravan stop of the ancient Sabaean empire.

At its peak about 3000 years ago, Tam'noh's vaults would have been full of frankincense, salt, spices and dried dates for the journey West to Africa and Europe. Today, these vaults and a single monolith are all that have been excavated. There are countless of unexcavated sites in Yemen and partially uncovered sites are seen all over the desert. Archaeological sites are unfettered by fences and barriers in these remote areas.

Our guides explained the history of the area and we were free to climb inside the vaults and to spend some moments in quiet meditation on the life and people of this caravanserai.

The silence was abruptly interrupted by the sound of bells and a child's voice, "La!"

A small boy threw stones at his herd of sheep as they rumbled over a nearby dune and scattered around our small group. The boy paused to say, "Hello!" then I watched them all run towards a small village in the distance.

"Sky! We go now!"

Ahmed opened the door to the Land Cruiser and offered me some water. We were off to another hidden temple.

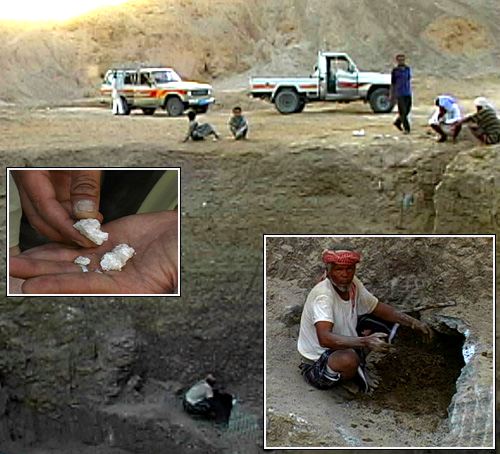

The Salt Mines

In the last place one might expect it, we found a product of the sea. Just outside of Shabwa the silence of the desert was punctuated by the iron clanging of an old but strong man, breaking up the stones and shoveling them with his hands.

"This man is digging for salt." Ahmed asked one of the workmen for a sample. "It is dug from deep in the ground and then it will be taken to the suq (market)."

No doubt that this type of rock salt would have been another item stored in the vaults of Tam'noh.

Shabwa

Over the next large dune we saw a collection of hills, rich with debris, stones and masonry. This was Shabwa -- the ancient capital city of the Wadi Hadhramout region. Most important capitals were built atop high mountains or in other strategic locations. We were curious why this old city had been located in such a seemingly dry and remote area. Ahmed explained that this ancient metropolis was situated near an oasis with a spring. It also watched over the old caravan route. Whoever controlled the water would rule the land. Whoever controlled the trade held the reins of the wealth. Shabwa had been in good shape back in 5th century AD.

Shabwa was more than a defensive position -- it was the religious center for the area. Over 60 stone temples have been discovered in this small archaeological site. The Main Temple was dedicated to the god Syn. The Palace of Shqr a remarkable structure built of purple granite, rose to six levels. Many of these stone walls remained standing despite their lack of mortar.

We were free to roam the ruins, inspecting the fragments and shards. One collection of rounded rocks was recognizable as a burying grounds. An inspection of the well preserved mounds showed that there were about as many females (2 upright stones) as males (one upright stone) and that the people were about 4 feet in height, on average.

|

As we left Shabwa, the afternoon heat was urging us to seek some relief. Traveling down the asphalt road brought us to the put-put-put of an irrigation diesel. Abdul didn't need to be persuaded. Soon we were parked next to the pump and a large reservoir of cool water. The men quickly stripped to their shorts and slipped into the cement pool. I was content to remove my hot veil and dunk my head in the water. Had I been alone, I would have loved to bathe there, surrounded by palm trees, exotic birds and the golden desert sun. Truly, water was the lifeblood of Yemen. The water in this reservoir had started its journey back in Marib, at the new dam, and it was now cooling my head on its way to nourish an orchard of fruit trees. The boys played and laughed before returning to the Land Cruiser. Refreshed and underway, we headed for a spot to pitch our tents among the Bedouins and to enjoy the thousand-and-one star hotel that was the Empty Quarter. |

|

Later that night, by our campfire, a Bedouin woman emerged from the darkness. Nah'ma was her name, the mother of our nomadic hosts. "She wants you to go with her," Nasser translated. I was taken by the hand and led to a large Bedouin tent. Inside, Nah'ma gestured to me to sit beside her on the wool carpet. A small candle was lit. Nah'ma produced a bundle from the depths of her wrappings.

Bedouins live throughout the Arabian desert and have dual citizenship with both Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Their nomadic lifestyle takes them to many remote and unknown archaeological sites. They often collect artifacts that they find in their migrations. These items can be very old and are brought to the surface after a strong wind or infrequent rain. A collection of such stone arrowheads caught my attention. They were small and delicate, yet pristine in condition. They appeared to be Paleolithic objects that could have been made millennia ago. I glanced quickly at my hostess. Only her eyes were visible but I could tell that my interest had been noted. The arrowheads were separated from the rest of the collection and moved in front of me. Now came the hard part: establishing the price. I had only a vague sense of the value of a Yemeni Ryal, but three thousand sounded a bit high. I countered with 1500, laying the cash on the blanket. The collection eventually sold for 2400. A black veil in the Bedouin style, a burqa'a, was added to my collection as a token of friendship. I later returned to the group, still by the fire, clutching my new treasures. I had to smile. I had just haggled for Paleolithic tools with a Bedouin woman in the middle of the Arabian desert! What was next? |

Previous Page || ViewZone || --next-->

A roll of burlap was carefully spread in front of me like a blank canvas. One by one, the veiled woman displayed stone tools and carved items that she and her family had found in the desert.

A roll of burlap was carefully spread in front of me like a blank canvas. One by one, the veiled woman displayed stone tools and carved items that she and her family had found in the desert.